The article is authored by Rasmus Nordfäldt Laws, senior associate in Moll Wendén’s Capital Markets Group, and Henric Stråth, responsible partner.

The article is written for informational purposes and should not be considered legal advice.

Introduction

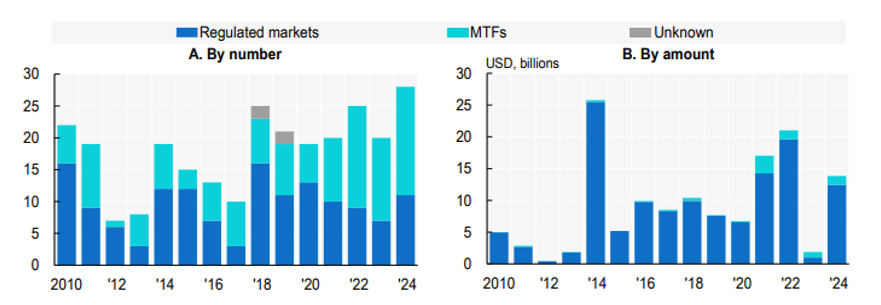

Public takeovers are common in Sweden. Between 2017 and 2024, an average of 21 takeovers were carried out per year. The proportion of takeovers of companies listed on MTFs (one of the growth markets Nasdaq First North, NGM Nordic SME or Spotlight Stock Market) has increased steadily and now accounts for more than half of the total number of completed takeovers in recent years. However, in terms of transaction value they are still underrepresented:[1]:

Since the MTFs were established in 2007, activity there has increased significantly. Over the past decade, approximately 80% of all listings have taken place on MTFs, which now account for almost two-thirds of all listed companies in Sweden. Although the total market capitalisation of MTF companies represents only 2.5%,[2] the statistics show a clear trend that partly explains the increasing takeover activity of MTF companies.

For growth companies listed on an MTF, which often have limited resources, navigating the legal framework in a takeover situation can be challenging. A takeover process may be initiated suddenly, making a basic understanding of the takeover rules essential. This article addresses this by discussing some of the issues that are most central for the target company in the event of a takeover bid.

The article does not cover takeovers on regulated markets (although the answers are similar) and all references to the Takeover Rules refer to the rules that apply to MTFs (not the equivalent for regulated markets).[3] Nor does it address mandatory bids (Sw. budpliktsbud) or takeovers with payment in transferable securities.[4] The Takeover Rules are not limited to Swedish limited companies, and the article is therefore also relevant for foreign target companies listed on an MTF in Sweden.[5]

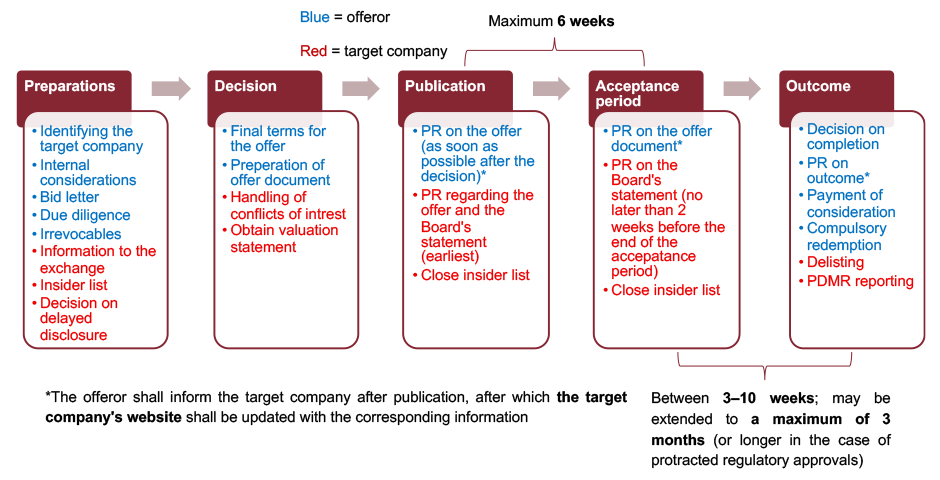

The takeover process

In public takeovers, the majority of the work rests with the offeror. As shown in the image above, the work includes identifying the target company; internal considerations, including securing financing and necessary permits (e.g. from competition authorities); sending an approach/indicative proposal (bid letter)[6] to the target company; conduct due diligence; entering into undertakings with the target company’s principal shareholders to accept the offer (irrevocables);[7] and preparing and publishing the offer document and press releases in accordance with the requirements set out in the Takeover Rules.

Although the bid is directed at the target company’s shareholders (and not at the company itself), the board of directors of the target company nevertheless plays a key role. The board is responsible for facilitating the bid by managing contacts with the offeror, assessing the fairness of the offer, and informing the market of its view of the offer. Since a bid is generally considered to be in the shareholders’ interest, the board may not take actions that impede the bid without shareholder approval (prohibition against defensive measures). Where a bid is serious, the board should normally cooperate with the offeror to a reasonable extent and ensure that shareholders are provided with a well-founded basis for decision-making.

Central issues for the target company concern: (1) disclosure of information to the offeror (including for due diligence and the offer document); (2) handling of inside information; (3) management of conflicts of interest; (4) preparation of the board’s statement and the obtaining of an external valuation of the target company’s shares (valuation statement);[8] and (5) persons discharging managerial responsibilities (PDMRs) and closed periods. These issues are discussed in more detail in the following.

Disclosure of information to the offeror

Listed companies are subject to far-reaching transparency requirements under, inter alia, the Market Abuse Regulation (MAR), the Prospectus Regulation, and the issuer Rulebook of the relevant trading venue. As a result, all material information about the company is already available to potential offerors. The need for access to additional information is therefore less pronounced than in private acquisitions. Nevertheless, offerors commonly request supplementary information from the target company, for example as part of their due diligence, for inclusion in the offer document, or for regulatory approval processes.

Such a request raises the question of whether the target company can and should cooperate in the disclosure of information and, if so, on what terms and to what extent.

First, it should be noted that the target company has no obligation towards the offeror to provide information. Refusing to disclose information is not a prohibited defensive measure nor otherwise contrary to Swedish capital markets law.[9] However, the board may risk breaching company law duties if it refuses disclosure. The board acts on behalf of the company (and, ultimately, the shareholders), and where a bid is serious and includes a reasonable premium, shareholders have a strong interest in being able to evaluate the offer. To fulfil its duties of loyalty and care towards shareholders, the board may therefore need to permit some degree of information disclosure.[10]

If the board decides to facilitate due diligence or otherwise disclose information to the offeror, such disclosure must, pursuant to section II.20 of the Takeover Rules,[11] be proportionate. The risks (e.g. disclosure of trade secrets and use of company resources) must be weighed against the benefits (the shareholders’ ability to assess the offer). Only information necessary for the bid may be disclosed, all disclosed information must be documented and protected by confidentiality, and any due diligence should be conducted within as short a timeframe as possible to avoid unnecessary disruption to the target company’s business.

From a MAR perspective, the question arises whether inside information may be included in such disclosures. This is generally permitted, as it may constitute a normal exercise of employment, profession or duties (10.1 MAR). A common question is whether the offeror must be included in the target company’s insider list under 18.1 MAR before information is disclosed. The answer is no: the target company is only required to keep a list of its “own” insiders (employees, board members, advisers, etc.), not external counterparties. Confidentiality must, however, be ensured prior to disclosure, for example through a non-disclosure agreement (17.8 MAR). If inside information is disclosed, it must be made public as soon as possible to eliminate information asymmetry between the offeror and the shareholders (II.20).

Handling of inside information

Under 7.1 MAR, inside information is non-public information of a precise nature which directly or indirectly concerns the company and which, if made public, would be likely to have a significant effect on the price of the company’s shares. If a listed growth company receives a bid letter from a party with the financial capacity to carry out the offer on reasonable terms, this will in practice almost always constitute inside information. The company must then, without delay, establish an insider list pursuant to 18.1 MAR and either immediately disclose the information under 17.1 MAR or delay disclosure pursuant to 17.4 MAR. Delayed disclosure requires that three conditions are met: (1) a legitimate interest, (2) that the delay does not mislead the public, and (3) that confidentiality can be ensured.

Takeovers are a textbook case where delayed disclosure is justified. It is in the interests of both the target company and the offeror that the share price does not react before the terms of the offer are finalised. If bid rumours spread, the share price may move in a way that causes the offeror to abandon the process. A legitimate interest in delay therefore exists, and delaying disclosure rarely misleads the public. Disclosure should therefore normally be delayed. Such a decision must be documented and the company’s Certified Adviser (for Nasdaq First North) or the trading venue (for NGM Nordic SME and Spotlight Stock Market) must be informed.[12] Notably, the trading venue has normally already been informed of the takeover interest, as the disclosure obligation under the trading venues’ Rulebook arises as soon as there is “reason to believe” that the preparations may lead to an offer.[13] In practice, this sometimes occurs as soon as shortly after the bid letter is received, and often when the target company’s board has decided to grant the offeror access to conduct a due diligence review.[14]

A prerequisite for delayed disclosure is that confidentiality can be ensured, which must be reassessed continuously. A takeover involves many parties – legal and financial advisers, the trading venue, auditors, principal shareholders and banks – and leaks of inside information do occur, as illustrated by the numerous insider trading investigations reported in the media.[15] In the event of a leak, the information must be disclosed immediately (via a leakage press release), as the conditions for delayed disclosure no longer apply.[16]

Delayed inside information is normally disclosed through the offeror’s press release announcing the offer. In connection with this, the target company must disclose its position on the offer, or state that its position will be announced later, with a reference to the offeror’s press release. In such a situation the question arises of whether the target company is disclosing inside information.

The prevailing view is that the information loses its character as inside information once the offeror has published its press release.[17] Consequently, the target company’s press release does not need to include a MAR label if it is published after the offeror’s announcement, provided that disclosure has been made in accordance with the distribution requirements in 17.1 MAR. In such cases, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority (the “SFSA”, Sw. Finansinspektionen) does not need to be notified of delayed disclosure. However, if both press releases are published simultaneously it is not incorrect to include a MAR label and notify the SFSA. If the target company’s press release also includes the board’s statement on the offer and that statement itself constitutes inside information, a MAR label must of course be included and the SFSA notified. Regardless of how or by whom inside information is disclosed, the insider list must be closed as soon as the press release has been published.

Upcoming regulation: New rules for disclosure under 17.1 MAR will come into force in July 2026, as Moll Wendén has previously written about (link here). The amendment means that intermediate steps in ongoing processes (e.g. receipt of a bid letter in a takeover process) will no longer need to be disclosed. Instead, disclosure will occur when the “final event” takes place. It is not entirely clear what constitutes the end of a takeover process (announcement of the offer, the board’s statement, or the outcome), but this is largely a theoretical issue: disclosure timing is governed by the Takeover Rules, and compliance with those rules will also result in correct disclosure timing under the new 17.1 MAR.[18] The timing of disclosure will therefore not change, but under the new rules the target company will no longer need to decide on delayed disclosure or notify the SFSA after publication. The information will, however, still constitute inside information, meaning that the company must continue to identify inside information when it arises, maintain an insider list, and monitor potential leaks.

Management of conflicts of interest

A conflict of interest arises where a member of the board or the CEO has an interest that conflicts with the shareholders’ interests. Under section II.18 of the Takeover Rules, such persons may not participate in the handling of the offer. In addition to board members or the CEO who are affiliated with the offeror (e.g. through shareholdings or employment), this also includes board members or the CEO who, in their capacity as shareholders in the target company, have entered into irrevocables with the offeror.

In cases of conflicts of interest, the board must assess whether it remains quorate under Chapter 8, Section 21 of the Swedish Companies Act (ABL). If the board is not quorate, it may not make binding decisions, including decisions on information disclosure, the board’s statement on the offer, or defensive measures.

In practice, it is common to establish an independent bid committee consisting of the non-conflicted board members. It is important to emphasise, however, that such a committee does not remedy a lack of quorum. The committee acts on behalf of the board and may only decide on takeover-related matters through valid delegation from a quorate board. Delegation is not possible if the board is not quorate.

To remedy a lack of quorum, it may be appropriate to appoint additional non-conflicted board members at a general meeting. Given the time and costs involved, this solution is not always practical. Neither is it a legal requirement, the target company may fulfil its obligations in connection with a takeover even without a quorate board, although this creates practical challenges.

Where a board member or senior executive participates in the offer, or where a parent company makes or participates in a public offer for shares in a subsidiary (a management buyout, MBO), special rules in Section IV of the Takeover Rules apply in addition to II.18. These rules aim to address the offeror’s informational advantage over the target company’s shareholders and include, inter alia, a minimum acceptance period of four weeks (IV.2) and, in the case of an MBO without a competing offer, a requirement to obtain a valuation statement (IV.3).

The board’s statement and valuation statement

According to II.19 of the Takeover Rules, the board of directors must publish its opinion on the offer and the reasons for it no later than two weeks before the end of the acceptance period. The statement must be clearly justified and provide guidance to shareholders. It is advantageous – but not a requirement –to include the board’s statement in the offer document (which must be published before the acceptance period begins).[19] If the board is not quorate, the non-disqualified members have the right (but not the obligation) to publish their opinion on the offer (II.19 paragraph 3).

The board’s statement is normally based on (at least) one valuation statement on the shares in the target company from an independent expert. This is mandatory if the board is not quorate due to conflicts of interest (II.19, paragraph 3) and, as mentioned above, in the case of an MBO without competing bids. However, it is also appropriate in other cases, as it strengthens the basis for decision-making and demonstrates that the matter is being handled with care in accordance with the board’s company law duties.

To be able to publish a well-substantiated valuation statement at the time the offer is announced – which is preferable where the offer is favourable – the target company should, as soon as the offeror’s seriousness and the reasonableness of the terms are established, obtain quotations from one or more independent valuation firms. The opinion may be obtained from an adviser in the transaction, but the fee must not be contingent on the size of the consideration, the level of acceptance, or whether the offer is completed.[20]

PDMRs and closed period

Acceptance of a takeover bid constitutes a transaction which PDMRs, as well as persons closely associated with them, must report to the SFSA within three business days from the transaction date (19.1 MAR). The transaction date is the date on which the offeror announces that all conditions have been satisfied or waived (the completion date).[21]

PDMRs are subject to a 30-calendar-day trading prohibition (closed period) prior to the publication of financial reports (19.11 MAR). During an ongoing offer, the company should consider adjusting reporting dates so that the acceptance period does not coincide with a closed period. If this is not possible (e.g. in hostile bids where the board does not control the timetable), grounds for granting an exemption from the trading prohibition may arise under 19.11 MAR and Delegated Regulation 2016/522. Such an exemption requires prior approval from the company. Even if approval is granted, acceptance is not allowed if the person holds inside information, which is often the case prior to financial reporting.

Conclusion

Sweden has a large number of listed growth companies that are increasingly becoming targets of takeovers. These companies do not always have internal resources with expertise in such processes, and the purpose of this article has therefore been to provide an overview of the most central issues the company needs to be aware of. Although the majority of the work in public takeovers is carried out by the offeror, the target company has several important obligations in order to maximise value for its shareholders.

At an initial stage, the target company needs to assess whether the offer is seriously intended and whether it is appropriate to disclose information to the offeror. If there is reason to believe that the bid will lead to an offer, the marketplace must be informed, either directly or indirectly via the company’s Certified Adviser. If the bid is serious, inside information will normally arise, and an insider list must therefore be established and a decision made on delayed disclosure. Any conflicts of interest within the board of directors and management must at the same time be identified and managed, and if PDMRs hold shares in the company, the transaction timetable should be planned in relation to the upcoming closed period. At a relatively early stage, a valuation statement should be obtained, and the board should otherwise prepare for the publication of its statement on the offer. Information leakage must be monitored for as long as disclosure of inside information has been delayed, and the company’s website must be continuously updated with information on the offeror’s offer, the board’s position, and the final offer document.

In order to navigate correctly and avoid pitfalls, our recommendation is to already at the stage of initial contacts with the offeror consider these issues and, where necessary, engage advisers for support.

Notes

[1] The table is taken from OECD’s report “The Swedish Equity Market” from 2025, see link here.

[2] OECD report above, page 13.

[3] The Swedish Equity Market Self-Regulatory Committee’s Takeover Rules for Certain Trading Platforms (1 July 2025).

[4] If the consideration consists of transferable securities, questions arise regarding, among other things, the obligation to publish a prospectus, the valuation of the consideration, and if a general meeting is required to resolve on the issue of securities.

[5] Note, however, that the Takeover Rules’ provisions on defensive measures (II.21) and mandatory bids (III) only apply to Swedish limited companies.

[6] A bid letter refers to a non-binding expression of interest/proposal to purchase the company. The letter often includes preliminary terms such as price, intended conditions for completion and consideration (shares or cash). The letter may also be conditional on the target company cooperating with regard to disclosure of information, recommending the offer, irrevocables being entered into, etc.

[7] Irrevocables refer to binding and irrevocable commitments to accept the bid, which are normally entered into before the bid is made public. Obtaining irrevocables reduces the offeror’s transaction risk by increasing the chance that the bid will reach the required level of acceptance. Irrevocables are therefore a central part of the preparatory phase of the bidding process.

[8] Valuation statements are often used synonymously with “fairness opinions”, i.e. statements on the fairness, from a financial point of view, of an offer to the shareholders of the target company.

[9] See AMN 2005:47 and AMN 2006:55.

[10] Cf. Stattin, Om due diligence-undersökningar vid takeover-erbjudanden, SvJT 2008, page 751 and forward (link here).

[11] The rule applies specifically to due diligence, but the principles should also be applicable to requests for information in general.

[12] See 6.2.5 of the Nasdaq First North rules, 4.3.3 of the NGM Nordic SME rules and 3.8 of the Spotlight Stock Market rules.

[13] See 6.2.3 of the Nasdaq First North rules, 4.3.1 of the NGM Nordic SME rules, and 5.1 of the Spotlight Stock Market rules.

[14] See Sjöman, EU Market Abuse Regulation and takeover bids, SvJT 2019, page 893 (link here).

[15] See, for example, DI’s article on 20 October 2025 (link here) on five current insider trading cases during the autumn, where information was leaked from Nasdaq, various banks, law firms and auditing firms in connection with several different bids in recent years.

[16] The offeror should (but is not required to) issue press releases regarding leaks, see II.3 paragraph 2 of the Takeover Rules.

[17] See Sjöman, EU Market Abuse Regulation and takeover bids, SvJT 2019, page 900 (link here).

[18] ESMA’s final report (link here) with a draft delegated regulation (see page 64 and forward) specifying when ongoing processes are to be disclosed under 17.1 MAR does not include any guidance specifically regarding public takeover bids. However, recital 12 states that the Regulation shall not affect the application of the Takeover Directive (2004/25/EC), which means that the obligation to disclose under MAR may not, in any case, take effect earlier than the corresponding obligation under the Takeover Rules.

[19] See item 4 of the Annex to the Takeover Rules.

[20] See paragraph two of the commentary on IV.3 of the Takeover Rules.

[21] Cf. recital 30 of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/522. In practice, it has been accepted that the transaction date may occur after the completion date if the consideration has in fact been transferred to the offeror only on that later date; see the judgment of the Administrative Court of Appeal (Sw. Kammarrätten) in case no. 3984-19.